Slashing government interest rates could have the paradoxical effect of raising the interest rates paid in the real world.

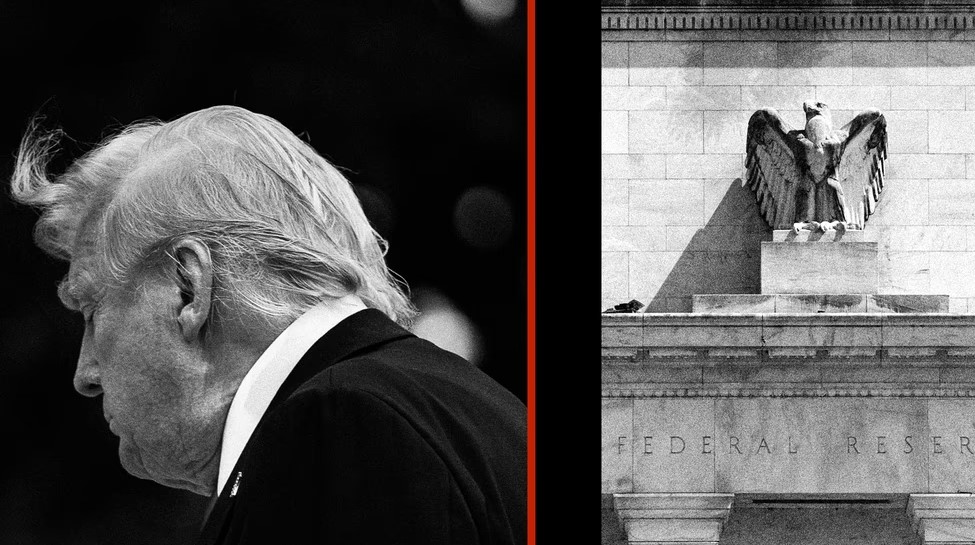

Donald Trump has so far gotten his way on tariffs and tax cuts, but one economic goal eludes him: lower interest rates. Reduced borrowing costs would in theory make homes and cars cheaper for consumers, help businesses invest in creating jobs, and allow the government to finance its massive debt load at a steep discount. In the president’s mind, only one obstacle stands in the way of this obvious economic win-win: the Federal Reserve.

Trump has mused publicly about replacing Fed Chair Jerome Powell since before he even took office, calling him “Too Late Powell” (as in waiting too long to cut rates) and a “numbskull.” Those threats have gotten more serious recently. In a meeting with House Republicans last Tuesday, the president reportedly showed off the draft of a letter that would have fired the Fed chair. Trump later claimed that it was “highly unlikely” that he would fire Powell, but he left open the possibility that the chair might have to “leave for fraud.” To that end, the administration has launched an investigation into Powell’s management of an expensive renovation of the central bank’s headquarters. (Any wrongdoing would, at least in theory, offer a legal pretext for firing him.)

This plan is unlikely to succeed in the near term. The administration’s legal case against Powell is almost certainly specious, and the Fed sets interest rates by the votes of 12 board members, not according to the chair’s sole discretion. Even if the president eventually does get his way, however, and installs enough pliant board members to slash government interest rates, this could have the paradoxical effect of raising the interest rates paid in the real world. If that happened, mortgages would get more expensive, businesses would have a harder time investing, and government financing would become even less sustainable.

Trump seems to have a simple mental model of monetary policy: The Federal Reserve unilaterally sets all of the interest rates across the entire economy. The reality is more complicated. The central bank controls what is known as the federal-funds rate, the interest rate at which banks loan one another money. A lower federal-funds rate means that banks can charge lower interest on the loans they issue. This generally causes rates on short-term debt, such as credit-card annual percentage rates and small-business loans, to fall.

But the interest rates that people care the most about are on long-term debt, such as mortgages and car loans. These are influenced less by the current federal-funds rate and more by expectations of what the economic environment will look like in the coming years, even decades. The Fed influences these long-term rates not only directly, by changing the federal-funds rate, but also indirectly by sending a signal about where the economy is headed.

What signal would the Fed be sending if it suddenly slashed the federal-funds rate from its current level of about 4.5 percent to Trump’s preferred 1 percent? Typically, an interest-rate cut of this magnitude would be reserved for a calamity in which the Fed drastically needs to increase the money supply to give the labor market a big boost. (This is what happened after the 2008 financial crisis.) Today’s economy has a very different problem: Unemployment is low, but inflation remains above the Fed’s target and has risen in recent months. In this environment, most economists predict that a dramatic increase in the money supply would send prices soaring.

Last week, in response to Trump flirting with the possibility of firing Powell, a key measure of investors’ long-term-inflation expectations spiked dramatically. The mere prospect of higher inflation is “kryptonite” for lenders and bondholders, Mark Zandi, the chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, told me, because it creates the risk that any debt paid back in the future will be worth a lot less than it is today. In such a situation, Zandi explained, banks and investors would likely impose a higher interest rate up front.

Many experts, including former Fed chairs, believe that cutting rates simply because the president demands it could have an even more profound consequence: It would tell the world that the U.S. central bank can no longer be trusted to credibly manage the money supply going forward. Investors would “get really nervous about holding U.S. Treasuries,” the economist Jason Furman told me, and demand a far higher return for buying them to make up for the higher risk—which would, perversely, drive interest rates higher, not lower. As evidence, Furman pointed out that, on several occasions, including last week, the interest rates on 10- and 30-year government bonds have shot up in response to Trump threatening to fire Powell. (In fact, the gap between short- and long-term rates jumped to its highest level since 2021 last week in the less-than-one-hour window between when reports surfaced about Trump planning to fire Powell and the president’s denial of that plan.) Because most long-term interest rates, including those for home mortgages, student loans, and auto loans, are directly pegged to the rate on government bonds—which serves as a sort of base rate for the entire financial system—all of those other rates would rise as well.